Save Our Fabulous Forests (for birds and wildlife)

England has lost nearly all its native woodland, with countries in mainland Europe enjoying far more forest cover (Latvia, Germany and Scandinavian countries all protect their woodland far better). A few years back, David Cameron’s government even tried to sell off our remaining public forests to private companies, until a petition at 38 Degrees stopped it.

Forests are not just as patchwork of trees. They are home to native birds and wildlife, provide clean air and are of course wonderful for a stroll (both for humans and dogs).

If walking in the woods with dogs, keep them away from conkers and learn toxic plants like bulbs and mushrooms to avoid. And trees to avoid near horses (including yew & oak).

Keep away from grey/white caterpillars (oak processionary moths can cause allergies and breathing difficulties). Also cordon off affected trees from livestock and horses. Mostly found in London in warm weather, report to your council and Treealert.

Public Forests Belong to Everyone

Forests are not just for humans. They provide berries and nuts and shelter for birds, food and homes for many creatures including badgers to deer.

The Scots pine is the only native pine in England, often found in old forests. Although pine trees are not safe near pets, they are great habitats for endangered red squirrels, providing food, shelter and therefore better immunity against Squirrelpox.

This is why you find more red squirrels in Northumberland and Scotland, where there are more pine forests. Culling grey squirrels is not the answer, a vaccination combined with better woodlands is. Read our post on saving all squirrels.

England’s Community Forests offers free, impartial advice and funding to farmers and landowners, to support you to plan and plant new woodlands.

How Lots of Forests Help the Planet

The more trees we have, the better we can soak up rainwater, and prevent urban heat island effect, as lots of trees help to provide shade and lower temperatures.

Forests are giant air filters, resulting in cities with lower rates of asthma and cleaner towns, cities and villages for everyone.

People were shocked at the chopping down of Sycamore Gap in Northumberland, as an act of eco-vandalism. But did you know that England’s second-oldest pear tree in Worcestershire was also chopped down, to make way for HS2 high-speed rail?

This project could kill 22,000 wildlife each year when built, when compared with TGV in France. Campaigners say money could instead by invested in better rolling stock and community transport. Barn Owl Trust says that HS2 is ‘a very expensive way of killing owls’.

What We Can Learn from German Forests

90% of Germany’s forests are heavily protected by law, and the 72 tree species are home to up to 10,000 animals and plants. Tree are so protected that there is even a word for it: Bannwald.

Can You Hear the Trees Talking? (by a German forester) is an interactive illustrated book for young readers, teaching how trees feel, communicate and take care of their families.

Learn about the ‘wood wide web’, aphids (who keep ants as pets!) and nature’s water filters. Also learn how trees get sick, and how we can help them to get better.

Trees sometimes nourish the stump of a felled tree for centuries after it was cut down, by feeding it sugars and other nutrients, so keeping it alive. If a tree falls in the forest, there are other trees listening.

When thick beeches support and nourish other trees, they remind me of a herd of elephants. They too look after their own, and help their sick and weak back up on their feet. They are even reluctant to abandon their dead. Peter Wohlleben

How Latvia Protects Its Native Forests

Latvia is home to one of Europe’s oldest languages, here you’ll also find Europe’s widest waterfall, and a country that is 50% protected forest. The country has a Forest Law to prevent protected zones being chopped down. 10% of Latvia is bog, so pack your natural rubber wellies!

England’s woodland wildlife faces many challenges. Old trees are rare, open glades get squeezed out, and planting trees by itself doesn’t bring back lost animals or plants. Woodland restoration needs more than saplings. Rich habitats, rewilding, and thoughtful care open the door for birds, insects, and mammals to return.

A recent report found that despite more tree-planting, our woodland wildlife and birds are still drastically reducing in numbers, mostly due to lack of heritage (older) trees and glades (open spaces).

If planting green spaces, read about pet-friendly gardens and wildlife-friendly gardens. And trees to avoid near horses (including yew, oak and sycamore).

Create More Woodland Glades

A glades woodland is a part of a forest where trees are spread out and sunlight can reach the ground. In these places, you will see grass, wildflowers, and sometimes small bushes growing between the trees. The ground is more open than in thick woods, so animals and insects can move around more easily.

In glades woodlands, you get a mix of shade and light. Some trees are close together, but there are lots of gaps. You won’t find very dense tree cover here. Because of all the space and light, many birds and butterflies love these areas.

Glades woodlands can look different depending on where they are. The soil might be thin, so big trees cannot grow everywhere. Sometimes rocks or little hills are in these spaces, adding to the variety. You will often hear birds calling and see light shifting on the ground as clouds pass by overhead.

These woodlands are important for plants and animals that cannot survive in dark, deep forests. They need sunlight or space to live. People also like walking in glades woodlands, as the paths feel bright and comfortable. They can spot wildflowers and hear lots of different sounds.

Overall, glades woodlands are lovely, open spots that bring a lot of life to a forest.

Protect and Restore Ancient Trees

Ancient trees are some of the oldest living things we have. Many have stood for hundreds of years. You will find them in woods, parks, and fields. Animals, birds, and insects make their homes in these trees. Moss and fungi grow on their bark. Owls, bats, and beetles rely on the spaces within old branches.

When we cut down or damage these trees, we take away shelter and food for wildlife. Animals lose a safe place to rest or raise their young. Plants that grew in the shade of these trees can also disappear. Not many new trees can replace all of this. Old trees hold secrets and support life that young ones cannot.

We need to look after ancient trees. Clear signs help people understand not to pick at bark or carve names.

It takes a long time for a tree to grow old and strong. If we save and restore ancient trees, we protect the wildlife around us. We give many plants and animals a better chance to live. When you see a really old tree, take a moment to notice all the life it holds. This is how nature stays balanced.

Encourage Natural Regeneration

When we talk about encouraging natural regeneration, we mean letting trees and plants grow back on their own, without planting new seeds. This can help bring nature back to areas where it has been lost. If we leave some land alone, old tree roots and seeds in the soil can wake up and start to grow.

Allowing this to happen gives birds, bugs, and animals places to live and eat. Leaves and branches from trees create shade and shelter. Flowers and fruits give food to many animals. Over time, more plants pop up, and insects, birds, and other creatures move in. The area starts to feel alive again.

Natural regeneration works best if we protect the land from people cutting down trees or letting animals eat all the small shoots. This way of letting nature repair itself costs less and often works better than planting lots of new trees. When we encourage natural regeneration, we help wildlife come back, support healthier soil, and keep the air cleaner. Letting trees and nature find their way back brings life and colour to the land.

Rewilding & Nature-Rich Habitats

Rewilding woodlands means letting nature take the lead. People stop tidying up certain forests or parks and let trees, plants, and old logs stay where they fall. Butterflies, birds, and all sorts of animals find food and safe places among the wild growth. As trees get older and new ones appear, the land feels more alive. Rewilding links woodlands to meadows, ponds, and wetlands, which helps bats, dormice, and warblers.

Animals like owls, hedgehogs, and foxes find more homes when the woods feel natural. Over time, water in ponds and streams gets cleaner. Wildflowers and insects come back. Mushrooms and moss thrive in damp, shady spots. Birds fill the air with song. All these things show the woodland is healthy.

Rewilding helps fix damage from the past, but it works best with patience. You see more life in the woods year by year. Many people visit these places to feel calm and closer to nature. Rewilding woodlands is a gentle way of giving back to the earth and helping wildlife at the same time.

Plant a Mix of Native Trees and Shrubs

When councils plant native trees and shrubs, this helps birds, insects, and animals. These plants belong in your area, so wildlife knows how to use them. Birds can build nests in their branches. Bees and butterflies can find food from the flowers. Small animals can hide among the leaves and roots.

Native trees and shrubs grow well without much help. They suit your local soil and weather, so they often need less water and fewer chemicals than other plants. Native plants give wildlife the right home and food they need.

Leave Deadwood and Fallen Logs

When you see deadwood and fallen logs in a park or forest, it might look messy at first. People sometimes think we should tidy up by removing them. But leaving deadwood and logs alone actually helps nature and wildlife like hedgehogs.

Many animals, birds, and insects use deadwood to live or find food. Beetles and ants hide under the bark. Woodpeckers dig holes to find bugs. Birds, frogs, and small mammals rest or nest inside hollow logs.

Fungi and moss grow on fallen wood and help break it down. This process returns nutrients to the soil. New trees and plants use these nutrients to grow strong. Deadwood and logs also help keep the ground damp by holding moisture, even when the weather is dry. They slow down rain, stopping soil from washing away.

Leaving deadwood gives support to many living things. It keeps forests and parks healthy, even if the area looks a bit wild. Next time you see a fallen log, remember it is useful, not just old wood.

Woodland Corridors and Linking Habitats

Woodland corridors are wide strips of trees and plants that link woods or forests. These paths help animals move from one place to another. Animals need to travel for food, water, shelter, or to find others of their kind. When woods and forests are spread apart, animals can get stuck in small spaces, which isn’t good for them.

A linking habitat does a similar job. It connects bits of natural land that might be cut off by roads, towns, or fields. Linking habitats give animals safe ways to move between these separated places. Birds, hedgehogs, foxes and other animals can all use these links. Linking habitats can be things like rows of trees, grassy strips, or even hedges.

If animals can move around, they stay healthier. They find better food and feel safer. Plants can also spread this way, as animals carry seeds through the corridors.

When people build new roads or houses, these links can break. If we keep woodland corridors and linking habitats, they help wildlife survive. Even small green paths between gardens, parks, and countryside can make a big difference. Keeping these links means we share the land with animals and plants, so everyone has a place to live.

Avoid Chemicals and Light Pollution

At night, keep outdoor lights low or off, as many creatures (including bats, moths, and owls) need darkness to thrive. This also helps to stop birds flying into windows.

Chemicals like bug sprays or weed killers can make animals sick. They can even make water and soil dirty, which hurts the places where animals live. Some birds, frogs and bugs are very sensitive. When chemicals get into their home, they can’t always recover.

Read our posts on:

Help Community Woodland Projects

Join or support conservation groups in your area. Community woodland projects bring people together to care for local forests and green spaces. Anyone who wants to help can take part. People may plant trees, clear away rubbish, or create safe paths for walking. Some may look after plants and animals that live in the woods. Others share information or help raise money.

These projects help trees grow healthy and strong. They also give people a place to relax, spot birds, or meet neighbours. You do not need any special skills to join. Most groups welcome extra hands, no matter your age.

Taking part in a woodland project feels good. Caring for nature and seeing the woods improve can make you feel proud. Even small efforts, like picking up bits of litter, make a difference. Over time, the woods can become greener, safer, and better for everyone who visits.

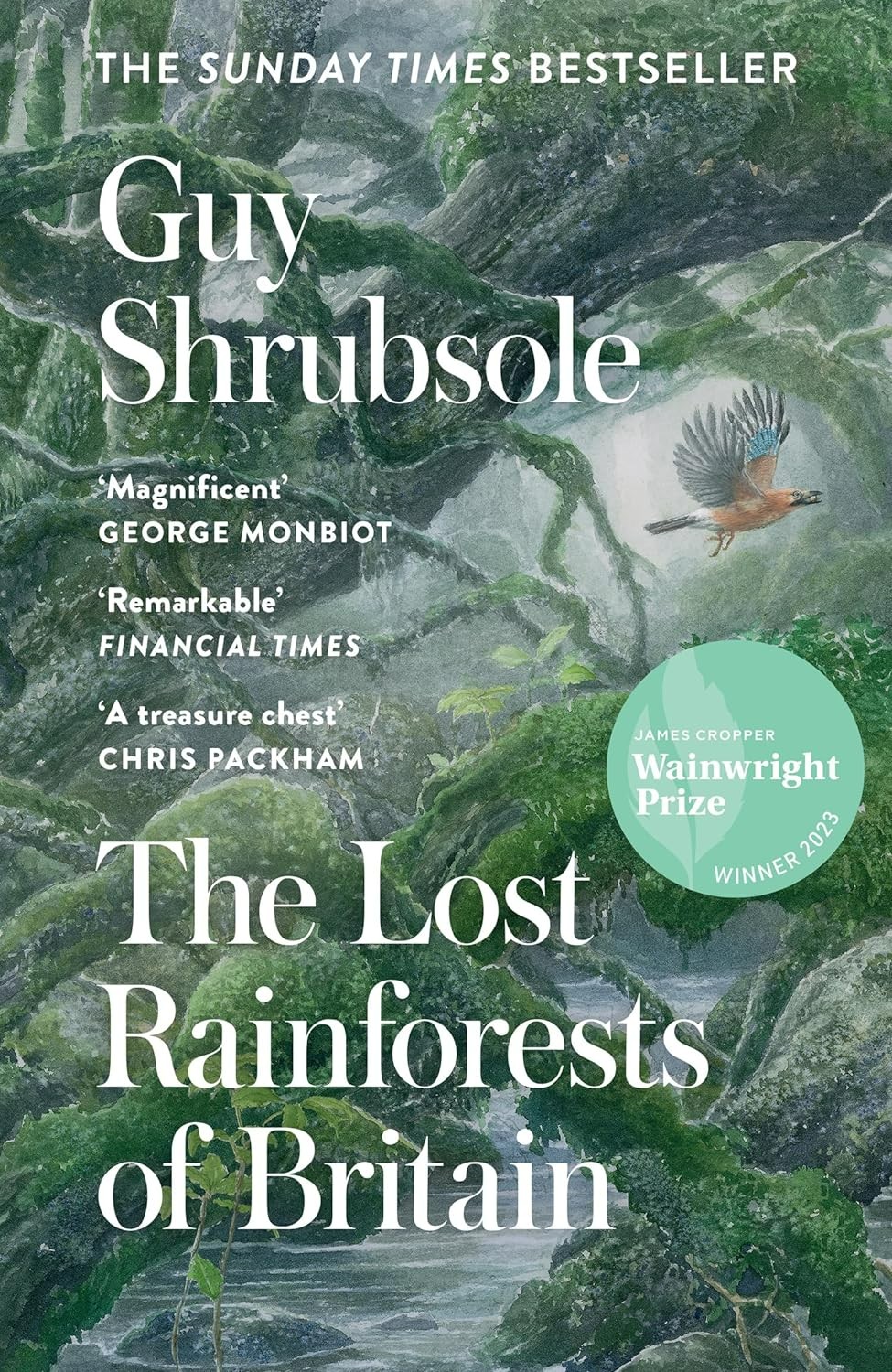

The Lost Rainforests of Britain is an award-winning book about the temperate rainforest that may once have covered a fifth of our land. Environmental writer Guy Shrubsole travels through the Western Highlands and the Lake District, down to the rainforests of Wales, Devon and Cornwall to map these spectacular lost worlds for the first time.

England does has many temperate rainforests (wet and mild which create canopies for woodland birds), which are as endangered as the Amazon rainforest. They are found in Devon, Cornwall and Cumbria.

Jay birds love acorns, so bury them in temperate rainforests. But they often forget where they put them, so they grow into new oak trees!

An Inspiring Personal Journey of Rewilding

An Irish Atlantic Rainforest is another award-winning book, by a man who rewilded a 73-acre farm he bought, on the Beara peninsula.

This is a story more of doing nothing than taking action – allowing natural ecosystems to return and thrive without interference, an in doing so, heal an ailing planet.