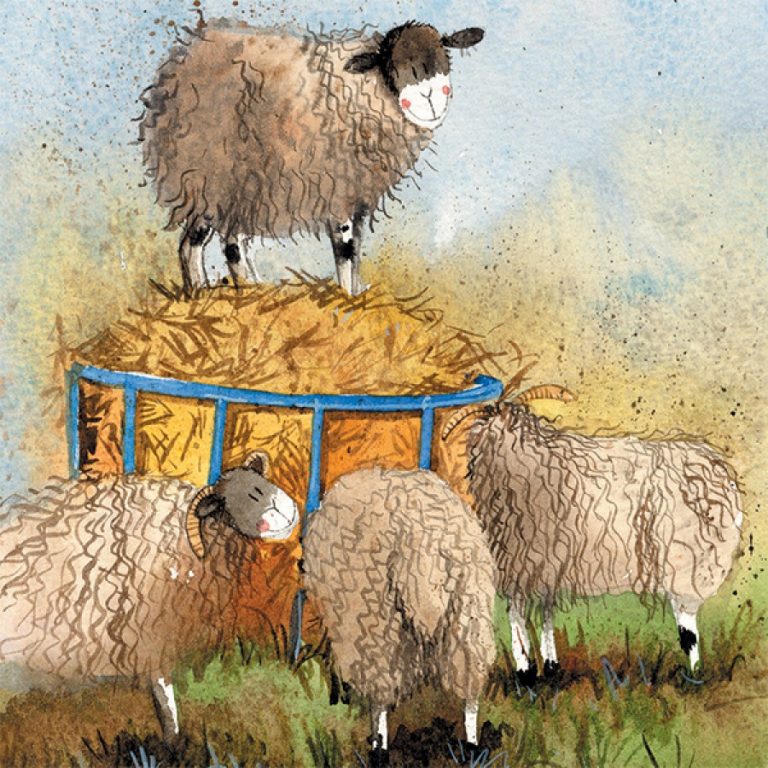

Cormorant, Holly Astle

As a land surrounded by sea, England has quite a few coastal birds. We can’t list them all here, but here are some of the most common species. Also read our posts on seaside gulls and puffins.

Keep at least 50 metres away from coastal birds (flying away wastes energy that could be spent feeding (they need extra space at high tide). Keep dogs away: disturbing nests can lead to abandoned chicks.

Sandpipers: Agile Shoreline Foragers

Sandpipers are more likely to be heard than seen, known for their distinctive three-note call. England’s common sandpiper has many relatives, including the USA’s spotted sandpiper (which sometimes visits) and the less common western and least sandpipers.

Sandpipers are beautiful coastal birds, known for their distinctive ‘bobbing’ movement where they move up and down, as they walk along, looking for food by the sea (they also live by lakes and estuaries, but can be found on the coast in southeast England).

This is called ‘teetering’, and sandpiper chicks begin to ‘bob’, almost as soon as they hatch from the eggs. The teetering becomes faster when birds are nervous, but stops if the bird is courting or alarmed.

Coastal Whimbrels (and their Seven Whistles)

Whimbrels have one of the most intriguing call, as it sounds like seven whistles. These birds have curved beaks and are smaller versions of curlews that breed on moorland and uplands, mostly seen at the coast when migrating. They eat insects, snails and slugs (and when migrating, switch to eating shrimp, molluscs and crustaceans).

You can tell them apart from whimbrels as they have blue-grey legs, shorter bills and a white wedge on their backs and tails (which you can see when they are in flight).

Whimbrels have mottled brown plumage, a trait shared with many shorebird relatives. This provides excellent camouflage against the sandy and rocky shores they frequent.

But what truly sets them apart is their long, down-curved beak, designed perfectly for foraging.

One of nature’s great travellers, whimbrels are known for their impressive migratory journeys. They breed in the Arctic tundra and migrate to warmer climates, often covering thousands of kilometres to winter in South America, Africa, and Australia.

Turnstones (strongmen of the coastal birds!)

Turnstones are medium-sized sandpipers, often found around rocky shores and gravel beaches. Named after their habit of ‘flipping’ large stones to find food. They are so strong, they can even lift big stones as heavy as them.

They are not native to England, but migrate here at different times. So can be seen throughout the year, depending on whether they have flown from Europe (spring/summer) or Canada/Greenland (early summer or autumn).

Turnstones have beautiful chequered black/chestnut patterns on their backs, with white patches elsewhere. But in winter, they change colour to dark brown with black patterns, retaining white bellies and chins.

Common sandpipers have green-brown backs (rock sandpipers have longer legs than turnstones, and much lighter plumage).

These birds eat a wide variety of food, and have been even known to eat discarded chips, washed up bodies and artificial sweeteners.

So it’s really important to take beach litter with you, as this is a species at risk of eating harmful items left behind (like plastic waste or cigarette butts), believing them to be food for chicks.

Sanderlings (that run like clockwork toys!)

Sanderlings are medium-sized sandpipers that feed in flocks at the tide edge, mostly eating insects, crustaceans, fish, worms and jellyfish.

They are not native to England, arriving from Greenland and Siberia in winter (sometimes on journeys of over 20,000 miles) and also ‘pass’ by during spring/summer migrations.

They are less stocky than most birds and you’ll often see them scampering on their three toes (due to missing a hind toe, wildlife experts say they kind of ‘run like a clockwork toy’).

Currently an ‘amber’ listed species, they are common on the Solent coast, where you’ll find them probing in the mud on sandy beaches for food.

Cormorants (truly excellent at fishing!)

Cormorants are spotted year-round, their feathers are not waterproof so can often be seen stretching out their wings to dry off, after using their excellent fishing skills to dive into the sea.

They use their long hook-tipped bills to swim underwater to eat, and tend to nest on low coastal cliffs or more recently, have started to fly inland to roost in trees (near lakes) and flooded gravel pits.

Large and black with white patches on their thighs during summer breeding, the younger birds are dark brown.

They look similar to (more numerous) shags, but the latter birds are smaller and are not seen away from coastal areas. They also have small ‘tufted crests’ dark green plumage and more narrow bills (with yellow gapes).

Choughs: Cornwall’s Beloved National Birds

Cornish choughs are similar to jackdaws. They are small black crows with glossy feathers, the difference being their long red legs and beaks.

A real conservation success story, choughs have come back from near extinction and are now successfully breeding, as the national birds of Cornwall.

Choughs live on short grassland and coastal heaths, and use their long red bills to eat beetle larvae and leatherjackets. They have a loud ‘chee-ow’ song, and are mostly found on cliff faces and rock ledges, but also nest in empty buildings.

The male chough is a good dad, who sticks around to raise the chicks! In fact, he pairs for life with his lady friend, and usually they return to the same breeding site each year.

Like most wildlife, the main threat to Cornish choughs has been modern agriculture practices. But Cornish conservationists have done a wonderful job, increasing the population by 60%, by helping to preserve habitats locally.

Preserving Habitats for Coastal Birds

England’s coastal birds claim a mix of habitats:

- Mudflats: Feast grounds for sandpipers and whimbrels at low tide.

- Rocky shores: Perfect for turnstones to hunt amongst crevices.

- Estuaries: Sheltered feeding spots where many birds gather in large flocks.

- Sandy beaches: The ideal racetrack for sanderlings.

Migration is key for many coastal species. Some arrive in spring to breed, while others pass through on journeys between the Arctic and Africa. As tides and seasons shift, so do bird numbers, making every visit to the coast a different experience.

Coastal birds face tough times. Their homes are shrinking due to building, pollution, and rising sea levels. Plastic waste and oil spills also threaten their food and safety.

But there is hope. Local wildlife trusts work to protect and restore vital habitats. They also clean beaches, and help local communities care for coastal birds. Legal protection and careful planning give these species a fighting chance.

Top spots for coastal birdwatching:

- Snettisham, Norfolk: Famous for breath-taking flocks of waders over the Wash.

- Spurn Point, Yorkshire: A migration hotspot, where almost anything can turn up.

- Farne Islands, Northumberland: Home to cormorants, terns, and puffins.

- Dungeness, Kent: A unique shingle headland rich with birdlife.

- Morecambe Bay, Lancashire: Vast sands attract huge gatherings of waders.

A pair of binoculars and some patience can open your eyes to this world, even on a weekend coastal walk.

This handsome shag bird art print is ideal to put on your wall of your home, office or independent shop. Sent in cardboard packaging with tissue paper, just place in your favourite picture frame.

Shag birds are glorious seabirds (related to cormorants), with glorious green eyes, long black necks and yellow patches around their mouths. They are often called ‘mini pterodactyls’ due to looking a bit like dinosaurs when they stretch out their wings.

Unlike most seabirds, shags don’t plunge into the sea to fish, but instead leap into the water, then dive down to find food. Like cormorants, their feathers are not waterproof (so they can dive deeper, but they have to dry their wings, after being in the water).

Shag birds like rocky coastlines and build their nests on cliffs using twigs, feathers and even seaweed, all held together by guano (droppings!)

Read more on England’s coastal birds, and how to help them.

Keep at least 50 metres away from coastal birds (flying away wastes energy that could be spent feeding (they need extra space at high tide). Keep dogs away: disturbing nests can lead to abandoned chicks.

About the Artist

Salthouse Studio was set up by a self-taught digital artist, who grew up in Scarborough (England’s first seaside resort, on East Yorkshire’s coast). Today she lives and works from her little studio in Liverpool, Merseyside.

Most of her prints are inspired by the salty sea coast of her childhood, her company brand named after one of the large docks on Liverpool waterfront.